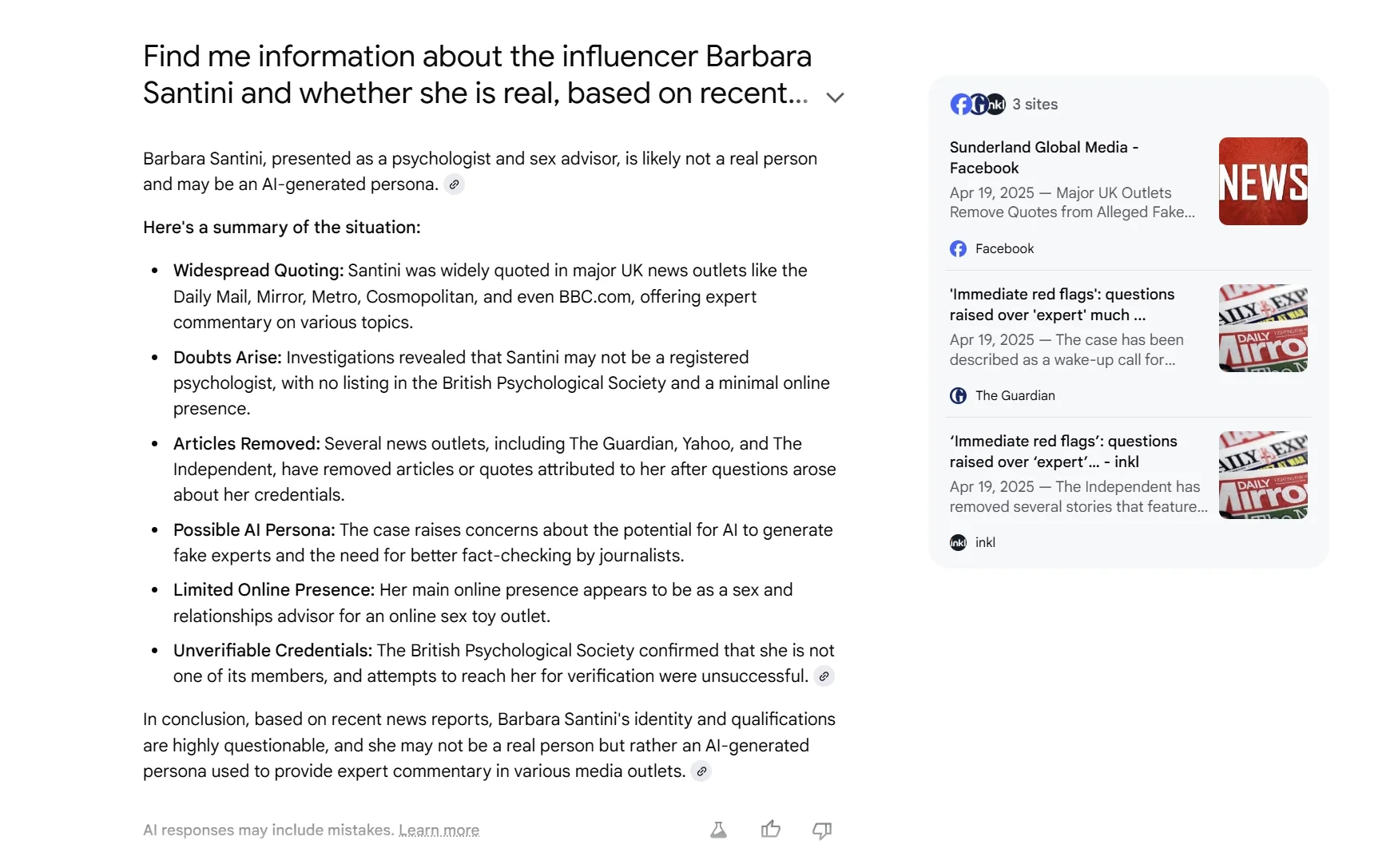

Invisible tax: Government debt is crushing your finances

Mortgage rates rose again this week, with the average 30-year fixed rate climbing past 6.8%. That’s not just a post-pandemic hangover; it’s a warning sign. Behind the scenes, rising government debt is putting steady upward pressure on borrowing costs.

If your mortgage, car loan, or credit card payments are more expensive than they were a few years ago, you’re not alone — and despite what you may have heard, it’s not just because of inflation or Federal Reserve policy. The surge in federal borrowing is helping inflate interest rates across the board.

If government debt had stayed at 2015 levels, the typical family could be paying $222 less per month on their mortgage. Go back to 2005 debt levels and the number jumps to $536. That’s real money disappearing from household budgets not because of the jump in home prices, but because Washington can’t stop borrowing.

DAVID MARCUS: WHY NOBODY WANTS TO CUT THE NATIONAL DEBT DESPITE EVERYONE SAYING THEY SHOULD

For years, economists puzzled over why interest rates kept falling. Aging populations, slower productivity, and foreign demand for American debt were all cited as reasons. One result was that Uncle Sam took advantage and racked up larger deficits and debt. After all, refinancing was affordable at low rates. Another was that Americans got used to lower monthly mortgage payments, auto loans, and other interest rate-related expenses.

Now, we’re grappling with interest rates that have surged and stayed stubbornly high. The change followed a torrent of unfunded federal spending in 2020 and especially 2021 which exploded the deficit, shook investor confidence in America’s long-term fiscal stability, and caused bond markets to react to policymakers’ fiscal bravado.

My new research for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, along with a growing body of economic literature, shows the debt itself is pushing up long-term interest rates — and by more than some experts are willing to admit. While broader economic changes and policy decisions also play roles, this particular problem is too big to ignore.

Over time, as trillions of dollars in debt compound, the Treasury shells out hundreds of billions more in interest payments. It’s not just a problem for Washington’s balance sheet. It’s a problem for yours.

Economists have a term for what’s happening: "crowding out." When the government borrows more, it competes with private borrowers for capital. And when two consumers want the same thing, the price usually goes up — in this case, the price of borrowing (interest rates).

All kinds of important things become more expensive: mortgage payments, car loans, student loans, credit card debt. These are not abstract concerns. They determine whether plenty of families can afford to buy a home, send someone to college or buy a new car or truck. They determine whether someone can start or expand a business and provide more people with jobs.

Take housing. Mortgage rates are now hovering near their highest levels in over 20 years. That’s not because lumber or labor costs spiked, but because of the effects of federal borrowing.

Student loan interest rates are tied to Treasury yields, which means college graduates are now repaying debt at the highest rates in almost two decades. Auto loan rates are rising too, pricing out lower-income consumers.

For Americans with credit card debt (almost half of U.S. households carry a balance) the average interest rate is now around 20%, driven in part by the same upward pressure caused by growing federal debt.

These debt-driven rate increases are an invisible tax on all of us. Families feel the squeeze every month. Businesses delay investments. Budding entrepreneurs face higher hurdles.

Why aren’t more economists talking about the problem? It’s complicated.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), for example, significantly underestimates the effect. Its latest projections assume long-term interest rates will stabilize at lower levels even as government debt as a share of the economy grows. But if debt pushes rates up more than the CBO predicts — as most empirical studies now show — then its rosy forecasts won’t reflect how much the federal government will pay just in interest.

Beyond our own households, there are consequences for the whole economy and government. Higher interest costs mean less money for education, infrastructure, or tax relief. They increase the risk of a debt spiral in which interest payments themselves become the fastest-growing part of the budget.

Most people understand that the federal government’s borrowing binge can’t go on forever, and that it will burden future generations of taxpayers. But if you’re between the ages of 19 and 99, the tax is probably already hitting you in some way each and every month. The cost of inaction isn’t just abstract and long-term, it’s concrete and already being felt.

Just check your mortgage statement.